In a conversation with Elena Mesropyan, Visa Innovation Centers, North America, Michael Jabbara, Senior Vice President, Global Head of Fraud Services, Visa, shares his observations on the evolution of payment fraud and how ecosystem participants can stay ahead of evolving threats to protect consumers and businesses.

Elena Mesropyan: Michael, how has the threats landscape evolved in your experience working in payments?

Michael Jabbara: Fundamentally, payments are made up of four components –

- you have buyers and sellers

- who are exchanging data

- over an infrastructure (whether that's physical like Point-of-Sale terminals, or digital like payment apps),

- and those exchanges are governed by a set of rules and regulations around liability, for instance, when a fraudulent dispute occurs.

Whether you're using your Visa card, crypto, or cash to make this purchase the same concept applies – you need these components. But these same components get targeted by fraudsters because they're looking for ways to subvert them for malicious gain. So, the targets don't change. What changes is the way that these components are targeted, and the intensity at which they're targeted.

Ten to twenty years ago, the core focus of these fraudsters was around data. What fraudsters were really interested in is how could they get payment data, print it on a bunch of mag stripe cards, and then make purchases with it, or withdraw ATM funds. However, a couple of things happened over time. We've invested a tremendous amount in token, EMV chip, and really sophisticated AI/ML fraud models that have made data much more secure. And even if there were to be a data compromise, if your data is tokenized, the data is completely useless to a fraudster. Only about 5% of total fraud on Visa network comes from compromised credentials, and it's going down significantly year over year because we've made it really hard to breach and monetize data.

But of course, fraudsters don’t just pack up shop, go to a coding bootcamp and all become developers. They started to think about where else they can target this value chain. They did a couple of things – they moved upstream from a data perspective, so they are no longer going after payment data, they are going after account data. They're going after the username and password, your name, your social security number, your email address, so they can create synthetic identities. And they were no longer targeting the physical infrastructure or not to the same extent as before (to get the data). They were targeting buyers and sellers; they were targeting consumers through things like social engineering and phishing scams. All of that because consumers are inherently vulnerable, because we have biases that can be exploited.

That’s how we’ve seen the evolution of payment fraud. The targets are the same, the methodologies are different, the intensity is different – all in response to the defenses that we put in place. It’s a continuous dynamic game between us and the fraudsters.

Elena Mesropyan: Let’s clarify for a moment – when we say “they” or “fraudsters,” who are we talking about, exactly? What characterizes them?

Michael Jabbara: There is this nostalgic view that a fraudster is this hooded individual in a basement, on their laptop. But that’s not what they look like. It’s not that you wouldn't have this kind of a rogue hacker here and there, but that's more of a figure of the popular imagination than a reality. The level of sophistication and organization for fraudsters has definitely increased. These entities are well-organized, well-funded, and operate very much like a business. They care deeply about their reputation and time to revenue.

We do a lot of monitoring of the dark web and there are entities that provide Ransomware-as-a-Service. You don't need to know how to build ransomware. You don't need to know how to deploy it. You can go to the dark web and there are these collectives that will partner with you to give you the tools, the training that you need to carry out these attacks. There’s some sort of commercial agreement that you strike with them to share the funds, for example, some offer profit split of 60/40.

But my personal favorite is when these groups stipulate who you can or cannot target. So, one group does not target hospitals and government infrastructure, i.e., if you use their service, you're not allowed to target these entities. You might think these are hackers with conscience, right? But that’s not what’s going on here. The reason why they don't want you to target hospitals and government infrastructure is because when you do that, it generates a tremendous amount of media attention and draws a heavy response from law enforcement. And because they operate like a business that cares about sustainable, long-term profitable growth, they don't want to go after a high-risk segment that could shut down their business. They have their own Chief Risk Officers who set the risk appetite. All this is to say that there is an increased level of professionalization these entities have in how they have set up their operations.

Elena Mesropyan: What a fascinating game of cat and mouse between comparably professional entities! Michael, you mentioned human biases that fraudsters exploit. Could you speak more about the human aspect of fraud? How do our behavioral and emotional triggers and biases play into fraud?

Michael Jabbara: Fraudsters are obsessed with the customer experience. They are really good marketers in the sense that they really think about designing experiences that allow them to yield the highest amount of success, whether that is stealing your sensitive data, your money, and then thinking about what emotional triggers they can leverage that would make consumers more likely to follow through the experience that was designed for them.

Think of how you and I shop – we go online, type in a good or a service, go through the results, click to go to an online store, add a product to the cart, pay, and then we're done. So, what fraudsters will do is they’ll create stores that look very similar to online stores where you and I shop, and they will manipulate the search engine optimization algorithms so that their link is one of the top results. It would look very similar to the real thing, and you’d click on it. If you weren’t paying really close attention, you wouldn't know any better. They have a very smooth checkout process. In the end, they’ve captured your information, and they can go on to monetize it by selling it on a dark web or to buy high ticket items.

And the other piece I mentioned is marketing. How do they attract people? They'll often generate marketing campaigns. For example, recently we talked a lot about back to school, this is top of mind for everyone. They’ll generate malicious advertising around back to school campaign deals. Most of these deals are very time-bound because they're trying to create an expectation that if you don't act now, you're going to lose it.

That is not by accident. Human beings are very loss-avoidant. All of these experiences, all of these triggers are well thought through. They’re refined, optimized, and launched at scale to maximize the amount of information and/or monetary value that's being harvested from consumers.

Elena Mesropyan: How has fraud moved along the transaction lifecycle, i.e., onboarding, authentication, authorization, dispute and optimization?

Michael Jabbara: Fraudsters never put all their eggs in one basket. They're looking to diversify the ways in which they accomplish their needs. Every part of that lifecycle has its own set of vulnerabilities that they look to exploit.

On the onboarding stage, they're looking to harvest your username and password so that they can take over your account, log into it, and then send funds out. In the authorization stage, they can carry out what we call testing attacks, where they'll generate a whole host of transactions that are looking to guess the 16-digit account number, the three digit code on the back, and then the expiry date. And when they get the right combination, then they'll go and monetize it again elsewhere.

On the dispute side, there are issues around things like first-party abuse, where you purchase something and because of the zero-liability rule, you will claim that it was actually not you who purchased it or that you never received the goods.

And then on the optimization side…there's so much complexity in the payment landscape, it can be challenging to get an end-to-end view of how payments are processed. So, if you you're not optimizing all your rules and all your configurations, the fraudster will find that one gap. And I think that's one of the most interesting things about fraudsters – they know payments incredibly well. They know how many digits each field should have and that if values are not populated, it's going to result in an auto approval, as an example. And if an issuer doesn’t know that and hasn’t set rules correctly, they could be out millions of dollars in a single attack.

Elena Mesropyan: Are there any parts of that lifecycle that have become more vulnerable over time? Or where fraudsters have become particularly good.

Michael Jabbara: It's certainly on the top part of the cycle, i.e., taking over identities, generating new card accounts, or creating synthetic identities. They are taking real pieces, like my name, your birth date, some other person’s address and social security number, and creating a net-new person and a new account with that individual. And since that individual doesn't exist, they can't really dispute the charges. So, the only time that you know it’s fraudulent is when they don't pay their account. And oftentimes you think it's a credit loss, when in fact it's a fraud loss.

There are also all these scams that occur where consumers are voluntarily giving their information away. They're making the purchase themselves. They will call the bank and say, “I actually want to make this transaction.” There was an incident relatively recently where we saw a cross-border transaction for a crypto purchase that was over $70,000, and we thought that was highly suspicious, and we let the bank know. The bank called the client, and the client said, “No, no, no, that is me who is making the transaction. Please let it go through.” But we still thought the transaction was suspicious. And then a few days later, the bank comes back to us and says, “Oh yes, that transaction actually did turn out to be fraudulent. The cardholder was scammed using a crypto investment scheme that they fell prey to through a social media ad and now they want their money back.” That's the challenge. Consumers actually want to make these transactions. To keep consumers safe, you have to do a lot of education and a lot of disrupting of the infrastructure that presents them with these scams.

Elena Mesropyan: It seems the human continues to be the most vulnerable point of failure. Some common scams, like romance scams, for example, really have to do with human vulnerability. People are also very open with private information on social media – you see people posting their travel plans, their tickets and passports. People volunteer sensitive information across platforms.

Michael Jabbara: That's correct, absolutely. Romance scams, in fact, are immensely popular and hugely profitable from a fraudster perspective.

Around February, we were doing heightened monitoring around romance scams because of Valentine's Day. Being the good marketers that they are, fraudsters are always looking to tailor their messaging for the holiday of the moment. And as part of our dark web monitoring, we came across this discussion between fraudsters who were talking about building chat agents that would pose as potential matches on online dating websites, carry on conversations with potential victims, and ask for money to be transferred into an account.

The interesting piece here is twofold. One, just like we are looking for ways to use genAI to make us more productive and automate our manual tasks, fraudsters also have a lot of interest in using that same technology for the same reasons, but for nefarious purposes. It’s also interesting how fraudsters discuss which dating sites they should target – can’t go to the biggest ones, because they are likely to have stronger controls, so they go one rung lower, to the ones with weaker security controls. Fraudsters are constantly looking for the weakest spots to target.

And the second part of that conversation that I found really interesting is their discussion about the cashout method. So, they create this agent, they get the victim on the hook, and now they need the victim to send them the money. How should they do it? Should they ask the victim to send the money through a P2P mobile app? A P2P crypto app? This is where they discuss demographics, i.e., if you're talking to an individual who happens to be on the older side, it's probably going to have to go through a wire or some sort of banking infrastructure. If you're talking to Gen Z, absolutely go through P2P or crypto route. So, fraudsters do segmentation when they are coming up with these scams.

Aside from romance scams, investments scams are also very popular – invest your money with a particular platform, and you are guaranteed a 20% return. You actually do see that return for the first few tries, and then when you put all your money into it, that's when the platform disappears. Or in worse situations, they'll say that the funds are there, but you need to pay a fee to get your funds out. And so, you pay the fee, and then you actually lose even more money. Even in those situations you'll see some incorporation of genAI because they'll create deep fakes of celebrities that endorse these fraudulent crypto trading platforms. People believe it and end up getting deep defrauded.

Elena Mesropyan: What attracts fraudsters to crypto?

Michael Jabbara: The intersection of crypto and fraud is twofold. One, if you think about the time-to-revenue aspect, when you go through a traditional cyberattack, essentially what you're looking to do is gain data that you then will sell on the dark web or data that you will use to buy high ticket items that you will then resell so that you can get cash. Really what you are thinking about as a fraudster is how do I convert my maliciously obtained assets into cash and. This is traditionally an extended process. But fraudsters realized that with cryptocurrency, the monetization cycle shrinks. All they have to do is get into somebody's system, lock it up, and demand crypto. And now they have actually monetized their illicit access. So, it's a much more efficient way for them to generate revenue. That’s one piece – there is a very direct correlation between the increase in adoption of crypto and an increase in incidents of ransomware because fraudsters found this way to go to market faster.

And the second key piece is when you look at it, and we’ll talk specifically about Bitcoin, the protocol itself is very secure because you have this decentralized consensus mechanism. But Bitcoin doesn't exist in a vacuum. It connects to on-ramps and off-ramps, and whenever you have a connection point, you have an entry point for a fraudster. What we have seen is that a lot of crypto thefts are happening from bridge services where you want to move traditional currency from platform A into a digital currency on platform B.

If you have a hermetically sealed financial system that's designed in a certain way, it will be foolproof. But if you wanted to interact with the real world, then you're creating points of vulnerability. And if you don't have a centralized security function that monitors for this, mitigates for it, and addresses those vulnerabilities, you're going to have an adverse selection problem.

To protect consumers in the crypto space, we look at the movement of funds in and out of crypto using Visa cards – we’re looking at potential fraud, money laundering, and ways that fraudsters are looking to use us as an illicit on-ramp or off-ramp. Let’s say you’ve stolen a bunch of crypto and now you want to convert it to cash and send it to a bunch of Visa debit cards through a push payment methodology. Well, we're going to notice – we’ll look at locality, accounts, their connections, volumes, and if all of it makes sense. If we're seeing a whole host of purchases of crypto using cards that are behaving in a very odd way, maybe they were involved in a breach, and now you’re monetizing that breach by buying crypto. So, we’re going to pick up on that. We’ve put in place defenses to safely enable crypto purchases and crypto withdrawals.

Elena Mesropyan: What are some emerging trends you are observing in the threats landscape?

Michael Jabbara: I get the privilege of reading a lot of dark web intel that our team generates. And I’ll give you a fascinating example: I mentioned genAI a couple of times and it’s something we are keeping a very close eye on.

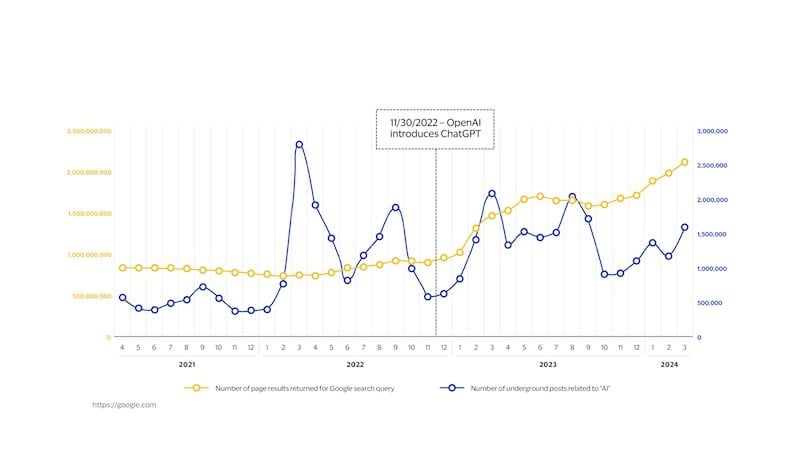

What’s interesting is that genAI mentions on the regular web have been consistent until ChatGPT came out and then the mentions spiked. But if you looked at the same graph for the dark web, you’ll see that there was a lot of interest in genAI even before ChatGPT came on the scene. And that's because people on the dark web were experimenting with things like deep fakes and voice manipulation way before they came into mainstream. And then when ChatGPT came, we see a relative slope of mentions on the dark web much steeper than on the regular web. On a relative basis, fraudsters were way more excited about ChatGPT than ordinary individuals because they saw the potential. They could see all the ways in which it can make their schemes much more successful.

Another thing that is a little bit further down the line is quantum computing and cryptography. Our entire financial system is built on cryptography. But quantum changes all of that. And we have already seen types of attacks that we call harvest now, decrypt later. So, fraudsters will breach a database. All the data is encrypted, so they can't use it. But they will hold on to it to a point where quantum computing or computing power gets powerful enough where they can go back and decrypt that data, and then monetize it accordingly. Quantum computing, from a commercial perspective, is probably five years away, but this shows you that fraudsters are long-term thinkers. They're looking to build long-term, sustainable profitable businesses. So they will plan ahead, they will adopt these technologies, and we need to continue responding appropriately. For example, the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) just came out with quantum proof standards that aim at moving the industry into encryption standards that won't be broken by quantum computing.

Elena Mesropyan: What is Visa doing to protect consumers?

Michael Jabbara: We take a multi-pronged approach to it.

One of the key components is really around consumer education. We spend a lot of time with our clients, with partners, with media to talk about the key threats that we're seeing, the top scams, and things that you should do to protect yourself. We create and publish our biannual threats report, which is a fantastic global lens into the fraud landscape and how consumers and businesses can protect themselves.

Second, we build network-level detections against fraud. Every transaction that gets processed on VisaNet, gets scored based on its risk. We also look at clusters of transactions across different clients, different geographies, different channels, so that we can detect these types of malicious patterns that can impact multiple parties and reach a large enough scale where we will intervene and will actively block the malicious activity on behalf of our clients. In fiscal year 2023, we proactively blocked $40 billion of volume that attempted to enter the network.

And finally, we also look to dismantle the actual infrastructure that's being used to carry out these attacks. When we start to see common linkages among accounts that are being used to carry out malicious activity, we can trace it back and assess how these accounts are created, where is the point of vulnerability, and shut it down with our partners and in partnership with law enforcement. And we've had several big successes where we shut down dark web marketplaces where the fraudsters buy their tools to carry out these types of attacks.

Elena Mesropyan: And finally, Michael, what is your recommendation for how our clients and partners can stay ahead of the evolving threats in payments?

Michael Jabbara: First, education is critical. If you don't understand the landscape, the threats, the taxonomy, what to look out for, then you're not able to stand up your defenses accordingly. Are you doing enough to educate your consumers about the threats that exist out there and what they can do about it? What are the right security habits that should be ingrained in them to make them seem less of a target? We are continuously monitoring the dark web and working with third party partners to understand how the landscape is evolving. We're continuously analyzing our data and refining our detections and mitigations so that we're keeping in lockstep with evolving threats.

Second, investments in the in the skillset and the individuals who know this space and can act as the human in the loop. Are you investing in the right talent and in developing your employees to counter the attackers? The funny thing here is that I come across so many really intelligent fraudsters who are great experts and I wish actually worked on our side. We have to really step up our game in terms of the talent that we train. AI/ML is a phenomenal tool, but it's only as good as the people who are deploying it. So, investing in the skillset is fundamental to success.

The third piece is really around technology, and I think about this in two ways. One, continuing to push for standards that get adopted across the entire ecosystem because this space is really dynamic – if we secure one endpoint, the risk is just going to migrate to the other. It’s only through collective action that we're able to make a difference. The best way to do that is through security standards like EMV, tokenization, and so on, to make the ecosystem more systematically resilient to attacks. That is how we can secure the ecosystem at scale. And then securing the nodes can be done through investments and things like AI/ML, and bringing in the data that we have to create more sophisticated and tailored models so that we can really pick up on these anomalies that come together without impacting the consumer experience. That’s really the challenge. It’s not necessarily about stopping the fraud, because it's very easy to stop fraud – just decline all the transactions. It's about making sure that the legitimate consumer isn't impacted. And finally, visit our brand-new Market Support Center in San Francisco to meet our experts; Visa can help our clients and partners understand and adapt to the evolving threats landscape.

And finally, visit our brand-new Market Support Center in San Francisco to meet our experts; Visa can help our clients and partners understand and adapt to the evolving threats landscape.

About Michael Jabbara, SVP, Global Head of Fraud Services, Visa

Michael Jabbara leads the Payment Fraud Disruption function for the Global Risk organization at Visa. His organization anticipates and mitigates large-scale payment security incidents and data breaches across Visa’s ecosystem by leveraging network-level intelligence and AI/ML-enabled capabilities. Prior to this role, he led the Global Risk Strategy & Operations team, analyzing market trends and changes in the Risk landscape, sharing relevant insights with key internal and external stakeholders, and re-assessing overall Risk strategic needs for Visa and its partners. Previously at Visa, he led strategic initiatives within Visa's Global Product commercialization group and managed the partnership program for Visa’s eCommerce solution, Cybersource.

Prior to joining Visa, he worked at Accenture in their Management Consulting group, focusing on business process redesign and organizational realignments projects within the Energy and Federal Government sectors.

He received an MBA from the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University and holds a BA in Economics from The College of William & Mary.